Spectacular vases, sensuous bowls, ornate beads, and, of course, snuff bottles are all items that have been crafted using the unique material known as Peking Glass. The glass has a luminous quality and incredible saturation of color. Thousands of decorative treasures utilizing this unique glass-making technique are housed in museums and art collections worldwide. Favored by the Imperial Palace of the Qing Dynasty in 18th century China, Peking Glass still holds its own today.

So, how did Peking Glass come about, and why does it deserve its own appellation? The Chinese have made glass since as early as the 3rd century BCE. Still, it was never a favored material, particularly by artisans and craftsmen. European missionaries brought new glass-making techniques to China in the 17th century, and the court was so impressed it established the Imperial Glassworks in the Forbidden City in 1696.

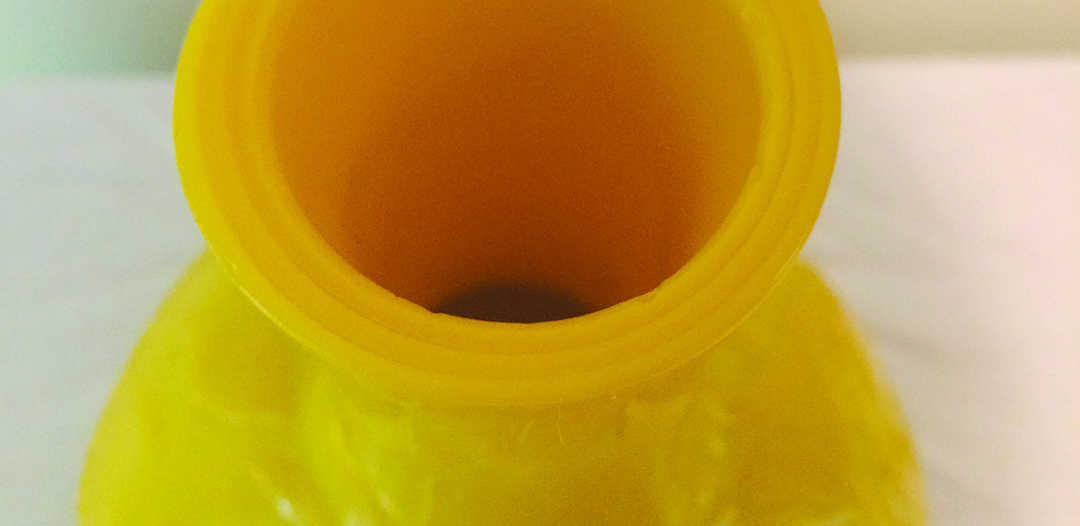

Peking Glass, also referred to as Chinese Overlay Carved Glass, is actually a method, not a material. A base object, such as a bowl, is repeatedly dipped into molten glass, creating layer upon infinitesimally thin layer over the base. The multiple layers are then carved away, leaving behind a textured and/or multicolored image. The traditional base glass color was usually clear or white, but could also be a deep red, Imperial Yellow — the color of the Qing Dynasty – and less often black. The ensuing layers of glass could be monochromatic, or they could vary.

Prior to the introduction of Peking Glass, imperial artisans made decorative objects primarily from precious and semi-precious stones such as jade, lapis lazuli, rubies, or ivory and horn. The method proliferated once the artisans learned these exceedingly thin layers of glass could be more easily carved into than the previously used stones. When deliberately exposed by carving, the colors of the layering glass imitate those of the more challenging materials. Favorite themes of the time included flora and small fauna, traditional symbols subjects such as peaches, the lotus flower, and koi, as well as Oriental landscapes.

Around the same time the Jesuit missionaries brought this glass-making technique to China, the Western habit of snuffing tobacco was widely gaining popularity in China’s high society. Decorative snuff bottles became all the rage among the elite Mandarin classes. The Imperial family used the extravagant ornamental glass snuff bottles produced at the Imperial Workshop to provide fashionable gifts to the courts and foreign diplomats. These highly coveted glass items included not only snuff bottles but also vases, bowls, and incense burners.

As with many fashions and trends, newer, more innovative, and cheaper production methods developed or spread to a broader, more common audience as time marched on. The allure of Imperial glass wares faded.

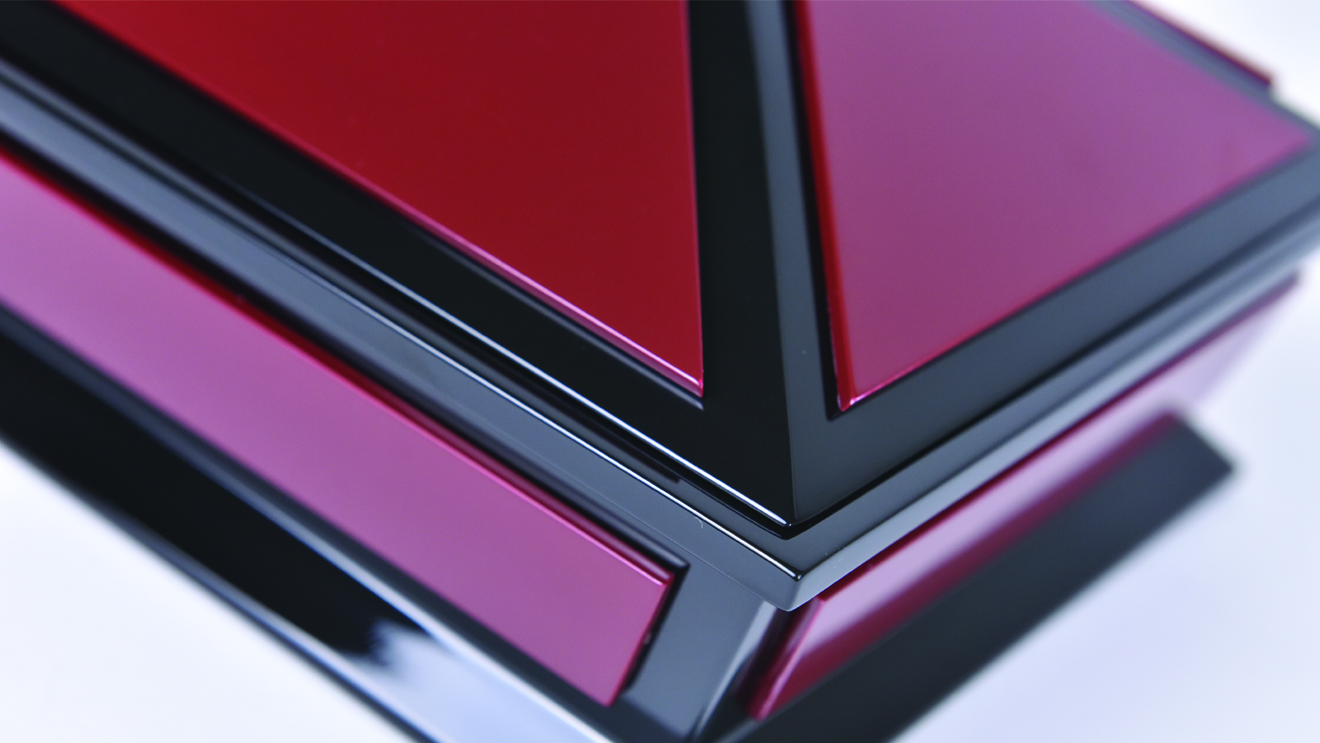

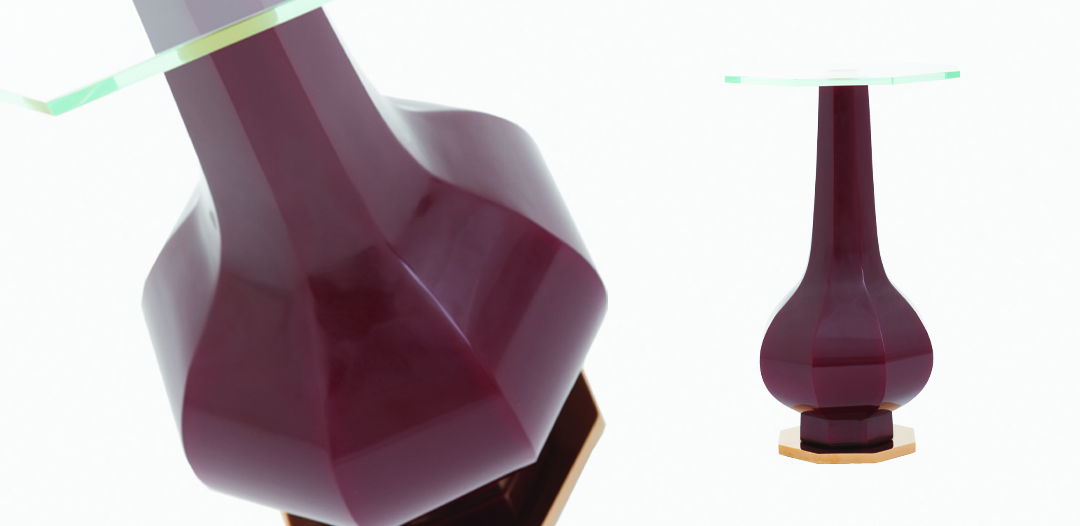

But fear not; we love its reintroduction to modern furnishings. The beauty of highly saturated colors on lamps and tabletops is unsurpassed. Decorative pieces shine with a luminescence so strong as to almost glow. Let’s elevate and revere this astoundingly beautiful glass technique, not snuff it out.

________________________

ERIC BRAND

Founded in 1996 and based in San Francisco, Eric Brand offers custom-styled furniture and worldwide sourcing along with exquisite materials and finishes, specifically for the high-end residential design market and hospitality industry.